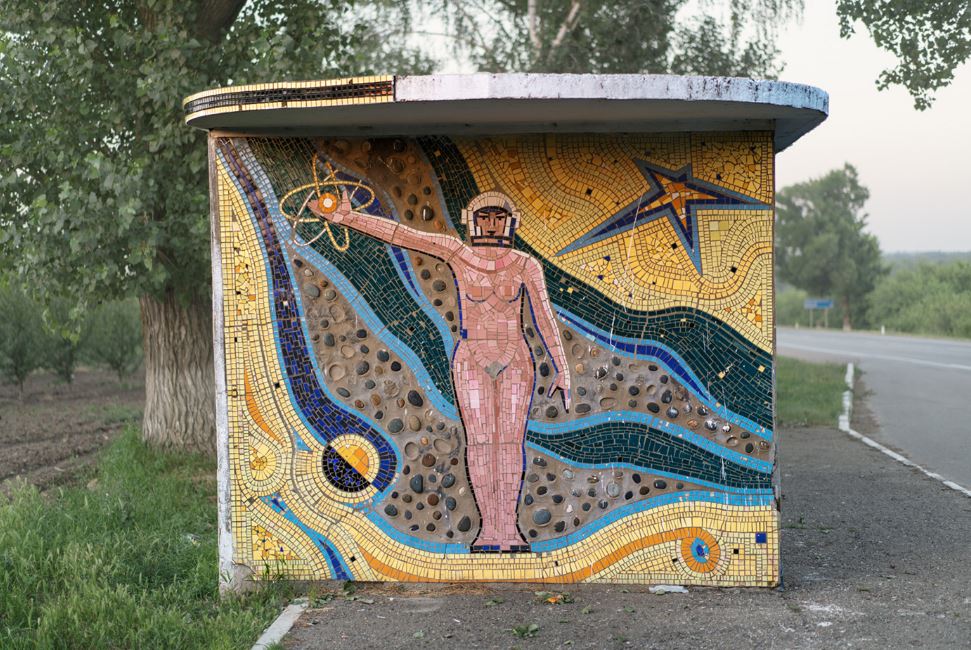

Building bus stops was a way to change the monotonous reality of Soviet times and architecture, and to emphasize the local.

In western Europe, the bus stop is the most humble of building types, a meanly utilitarian structure that adds little or nothing to the roadside. But in the old Soviet empire, from the shores of the Black Sea to the Kazakh steppe, the norm is “wild going on savage”, as Jonathan Meades writes in a beautiful new photobook featuring 159 bus stops, each illuminating “the Soviet empire’s taste for the utterly fantastical”.

Photographer Christopher Herwig has circled the former Soviet Union, exploring the most remote areas of Georgia, Russia, and Ukraine to find and photograph its unique bus stops. After the success of his first book Soviet Bus Stops, he decided to explore the subject matter again for his new follow-up collection Soviet Bus Stops Volume II. In this book Herwig focuses on Russia rather than its former Soviet counterparts, driving nearly 10,000 miles around the massive country finding its incredibly diverse transportation shelters.

For the book, Herwig photographed more than 150 bus stops in 13 different countries. He estimates that over the course of a dozen years, he took more than 9,000 photos of these whimsical structures. Most of the photos were the result of happenstance encounters while he was on assignment for various publications. Others were part of a more deliberate scavenger hunt where he’d map out a route of stops he found by scouring Google street view.

Herwig first started noticing the oddly-designed stations during an epic bike ride from London to Moscow, back in 2002. His first photograph was of a simple rectangular shelter somewhere in Central Asia. “It was just so different, thought-out, and quirky,” he recalls. “Like someone with a bit of a design eye was having a good time designing this thing.” Herwig quickly discovered that this wasn’t an architectural fluke. Similarly ornate bus stops were scattered throughout the region, punctuating the otherwise functional skylines of the former Soviet Union with a healthy dose of weird.

“I rarely found anything cool within a city,” Herwig explains. The most elaborate structures were often located in the countryside where they’d be the only stop for long stretches of road. Herwig says that many of the structures fell under the purview of the government’s roads department and were largely built in the ’70s, during a time when Soviet architecture centered around a mass-produced brutalist aesthetic. In an interview with Herwig, Belarusian architect Armen Sardarov explains that transportation was a point of pride for the Soviet Union, which is part of the reason architects could take so many chances.“We lived in a socialist world. In the socialist world individual transport was discouraged, it was not highly developed, we did not have cars on a massive scale,” he says. “The whole system was built on bus routes… they united the country.”

In that way, the bus stops then were almost like architectural mascots for villages. They reflected their surroundings through materials, colors, and shapes. In Belarus, for example, many of the bus stops were built by the villagers and incorporated rubble stones. In Estonia, most were made from wood. Others—like Tsereteli’s designs along the Soviet Riviera, where Nikita Khrushchev had a summer home—were far more ornate. These follies were considered minor architectural forms, Herwig explains; the low stakes and budgets associated with building them allowed for an aesthetic freedom otherwise unknown in the region. “People could get away with whatever they wanted,” he says.

This lead to some truly bizarre forms. One bus stop in Taraz, Khazakstan is sheet of folded steel propped up by two legs and contorted into a spaceship-like shape. Another, in Rokiskis, Lithuania, is a simple concrete rectangle painted neon yellow and green. The least practical of them all is another Tsereteli masterpiece in Abkhazia, that features a bench with an open, crown-like structure overhead. You wouldn’t want to rely on many of these bus stops during the region’s cold, harsh winters, but as Tsereteli explained when asked about the questionable practicality of his bus stops, functionality was never really the point: “I cannot speak to why there is no roof,” he says. Why this, why that—that’s their problem. As an artist, I must do everything artistically.”

The bus stop was one of the few building types that was blessed with a certain amount of autonomy from the centralised planning machine. Indeed, it was a government stipulation that they should be beautiful and reflect a local aesthetic.

Prof Konstantinas Jakovlevas-Mateckis, who was the head of road design in Lithuania in the late 1960s, recalls the sense of civic pride bus stops embodied: “We wanted the first well-ordained, landscaped highway to be the face of two cities – Vilnius and Kaunas. Building bus stops was a way to change the monotonous reality of Soviet times and architecture, and to emphasise the local.”

Consequently, in Kyrgyzstan there are bus stops shaped like the region’s high-crowned kalpak hats, as well as round tapering structures modelled on local yurts. Coloured concrete reliefs rule in the Ukraine, as do mosaics in Moldova, while in the forests of Estonia many bus stops are simple triangular pitched-roof structures, made of the timber that was to hand.

Some of the most elaborate structures occur around Pitsunda on the Black Sea, where Khrushchev had his summer dacha. Along these coastal roads, voluptuous sea shells compete with the gaping mouths of gigantic fish, writhing concrete forms heavily encrusted with mosaic tiles, like Gaudí at the seaside. They are mostly the work of Georgian sculptor and architect Zurab Tsereteli, now a celebrated Moscow-based artist and president of the Russian Academy of Arts. “We had a committee, an architectural and construction council,” he recalls. “I suggested that these bus stops shouldn’t be about just a frame, glass and seating. People should get pleasure out of them. We decided they should be monumental art in space.”

Images from photographer Christopher Herwig’s book ‘Soviet Bus Stops.’ & “Soviet Bus Stops – Volume II” Mr. Herwig has traveled through the former Soviet Union finding and photographing old bus stops for more than a decade.

Suggested Read: Moscow Metro Station Art – The Most beautiful Subway System In The World