Trümmerfrau (literally translated as ruins woman or rubble woman) is the German-language name for women who, in the aftermath of World War II, helped clear and reconstruct the bombed cities of Germany and Austria.

With hundreds of cities having suffered significant bombing and firestorm damage through aerial attacks and ground war. So, with many men dead or prisoners of war, this monumental task fell to a large degree on women.

Trümmerfrauen – The Women Who Helped Rebuild Germany After Second World War

A symbol of the German people’s wish to rebuild and of their powers of survival.

– Helmut Kohl

What role did German women play in rubble clearing after the Second World War?

In May 1945, Germany’s cities were buried under an estimated 400 million cubic metres of rubble. To give you an idea of the scale of this, if the rubble had been piled up on an area roughly the size of ten football pitches, this mountain would be as tall as the Montblanc, its summit permanently covered in snow.

In Hamburg, for example, which had suffered devastating attacks in July 1943, fifty per cent of the city’s housing stock was completely destroyed, and only about 25 percent remained undamaged. After the war, one of Hamburg’s main challenges was to remove about 43 million cubic meters of rubble.

Dresden, iconic for the destruction of its historic city centre in February 1945, faced a similar challenge, and this experience was repeated all over Germany.

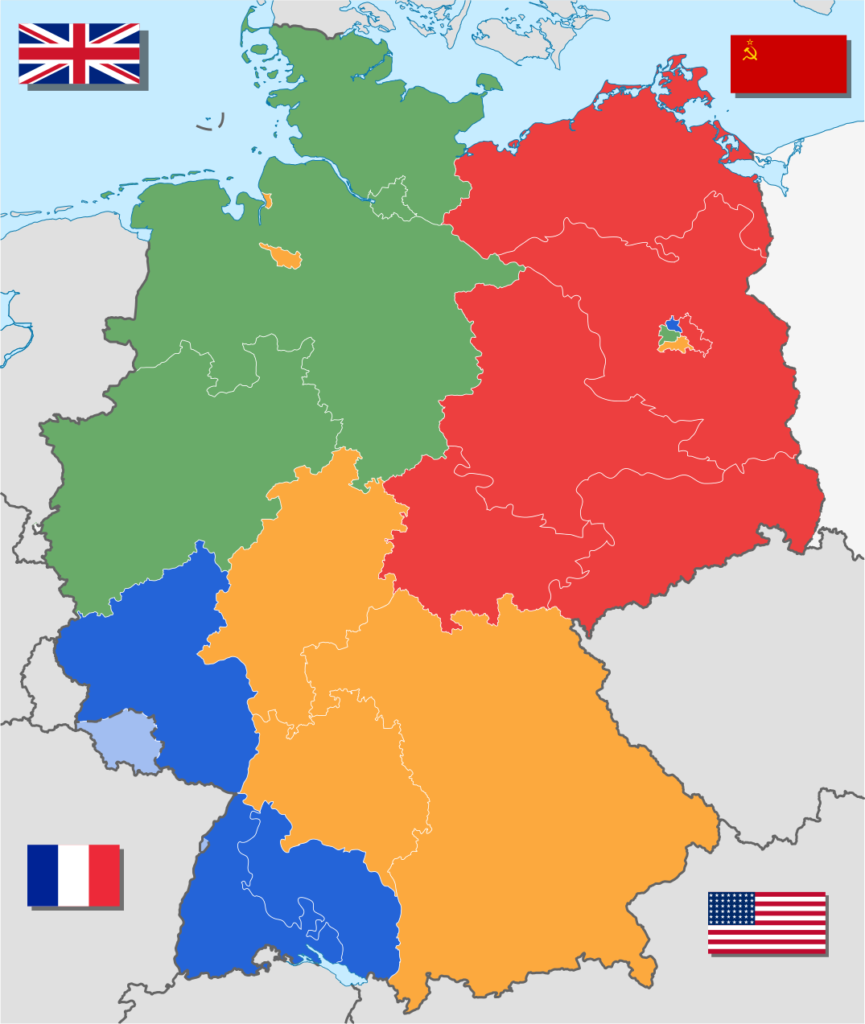

Between 1945 and 1946, the Allied powers, in both West Germany and East Germany, ordered all women between 15 and 50 years of age to participate in the postwar cleanup. For this purpose, previous restrictive measures protecting women in the labor force were removed in July 1946. Recruitment of women was especially useful since at that time, because of the loss of men in the war, there were seven million more women than men in Germany.

As these pictures reveal, clearing the rubble and rebuilding these cities was a momentous task, and it would take many years to accomplish.

Degree Of Damage: 3.6 million out of the sixteen million homes in 62 cities in Germany were destroyed during Allied bombings in World War II, with another four million damaged. Half of all school buildings, forty percent of the infrastructure, and many factories were either damaged or destroyed. According to estimates, there were about 400 million cubic metres of ruins and 7.5 million people were made homeless.

The task of removing the ruins were assigned to private enterprises, who in turn employed the women. The main work was to tear down those parts of buildings that had survived the bombings, but were unsafe and unsuitable for reconstruction. Using sledge-hammers, picks, buckets and hand-winches, each ruin was torn down and the rubble demolished further down to the bricks so that they could be reused later in rebuilding. A chain of women would transfer the bricks to the street, where they were cleaned and stacked. Wood and steel beams, fireplaces, wash basins, toilets, pipes and other household items were collected to be reused. The remaining debris was then removed by barrows, wagons and lorries. Many of debris these were used to fill up bomb craters and trenches. Others were piled up to form hillocks known as schuttberge, or debris mountains.

Trümmerfrauen, both volunteers and regular workers, worked in all weather. They were organised in Kolonnen (columns) of ten to twenty people.

Average workday & pay of Trümmerfrauen

The average workday of a Trümmerfrau was nine hours long with one 20-30 minute lunch break. The women were paid at a rate of 72 Reichspfennige (Pfennig) per hour along with one food ration card. This card could only feed one person a day. The issue was not in what one could do once they had the food, but dealt with the fact that the ration card gave very little food.

For comparison (1945):

* One loaf of bread = 80 Marks

* One pound of butter = 600 Marks

* One cigarette = 10 Marks

Dismantling the German myth of ‘Trümmerfrauen’

The image of hard-working, cheerful women clearing the rubble of WWII from German streets is deeply ingrained in German minds. But it’s only true to a certain degree, says German historian Leonie Treber.

Recent research by German historians has shown that NOT all rubble women were volunteers—selfless housewives in service to the nation, but Nazi functionaries who were forced to work by the Allies. Others were driven to the mountains of rubble by unemployment and hunger. In the university in Freiburg, students were required to clear rubble in order to be allowed to register for their studies. So while many women took part in rubble clearing they did not do it for altruistic reasons.

Booming business for construction companies

The historian concedes that, of course, the builders needed help – after all, about 400 million cubic meters of rubble and ruins were waiting to be cleared across the nation.

“But women played a minor role in clearing German cities from the rubble,” Treber says. Berlin mobilized about 60,000 women to clear the war ruins, but even that amounted to no more than 5 percent of the female population – it wasn’t a mass phenomenon. In the British Sector, Treber says, only 0.3 percent of the women joined in the hard work.

Yet it wasn’t just the women who were reserved when it came to clearing the war debris; men weren’t crazy about the task, either. In the eyes of the Germans, it was anything but honorable for people to show their “willingness to rebuild.” In fact, most Germans regarded clearing rubble as punishment – and for a reason.

During the war, the Nazis made soldiers, the Hitler Youth, forced laborers, prisoners of war and concentration camp prisoners clear the bombed cities after Allied air raids. In 1945, after the end of the war, prisoners of war and former members of the NSDAP Nazi party took their place. When that turned out to be insufficient, the population was asked to help – on a voluntary basis in the West, but usually against their will in the Soviet occupation zone.

Marketing the rubble women

Berlin won women over for the job by offering them the second-highest category of food ration cards. To get more volunteers to pitch in, authorities deliberately marketed the image of the cheerful Trümmerfrau at work, Treber says. That very picture is deeply ingrained in the collective German memory. “It’s evoked time and again in speeches, movies and books,” she says.

Initially, the media campaign was successful only in East Germany, where the rubble-clearing woman became a role model for all women who wanted to train for traditional male jobs. In West Germany, however, the hard-working, self-assured, emancipated woman didn’t fit the conservative female image.

Little wonder that Lisa Albrecht, a Social Democratic politician from the southern state of Bavaria, was shocked when she visited bombed-out Berlin in 1948. “I was appalled at the sight of the rubble women clearing Berlin,” she wrote.

Myths and Realities of Rubble Women

However, the memory does not stand up to scrutiny, as recent research by German historians has shown. For a start, rubble clearing was not altruistic or voluntary. In fact, it was initially a punishment.

During the war, prisoners, forced labourers (including some non-German women), and concentration camp inmates had been forced to clear rubble – often in dangerous conditions.

And in the immediate aftermath of the war, the Allies made German prisoners of war and former Nazi Party members move rubble as punishment. This included female NSDAP members. Thus, at least during and immediately after the war, clearing rubble had no positive connotations. It was not a heroic deed, but a punishment, and Germans clearly regarded it as such.

After the war, rubble clearing was also demanded of the unemployed in return for food rations. This was an experience widely shared across all of Germany, but different approaches developed in Eastern and Western zones of occupation. In the Soviet Zone of Occupation in the East, unemployed women and men were required to do this work, and due to lack of men, for a short while women formed the majority of this workforce.

In the West, unemployed women were only used for rubble clearing in the British zone of occupation, and only in small numbers. In what would become West Germany, the prevailing view was that this type of dangerous, hard work was not suitable for women. As soon as it was practicable, the authorities here favoured a move back to ‘womanly’ work and ideally a return to the home, leaving the heavy work of rubble clearing to men and to machines.

Early photographs of women clearing rubble are likely to show women who had been forced into this work, as punishment or through economic circumstances – rubble clearing entitled women in West Germany to additional rations, usually only allocated to heavy workers, and could save the lives of their families. Or, as in this image which I used above to illustrate Helmut Kohl’s version of German rubble women, they might depict women working in completely different circumstances. This image is of university students in Freiburg who were required to clear rubble in order to be allowed to register for their studies. So while these young women did indeed clear rubble, they did not do so for altruistic reasons. These are not the women of Kohl’s recollections, or of German national memory.

Increasingly, the West German population was also invited to volunteer for this task. However, most appeals were directed only at German men. Across West-Germany, the population was asked to donate a small number of days to this clearing-up effort (with much media campaigning to make this a palatable proposition). But – contrary to what Germans collectively remember – public appeals were not generally met with much enthusiasm by women.

For example, in a voluntary recruitment drive in Duisburg in the West German industrial Ruhr-area in December 1945, 10,550 men volunteered – and 50 women. Such evidence suggests that when they were not compelled to do so, German women did not volunteer in great numbers.

Overall, women did not play a major role in rubble clearing; rather, they were in a minority. Men and – increasingly – machines cleared Germany from the rubble – at least in West Germany.