Medieval kings spent a lot of time traveling around their realm from place to place. One of the duties of a vassal was offering hospitality to the king and his entourage if he chose to pay a visit – which could get very expensive, since kings always traveled with a large number of guards, ministers, servants and companions befitting their status. Indeed, one of the purposes of such visits was to make sure the subjects were reminded who their king was, and to give him the opportunity to inspect things in person.

Still, for the purpose of this description we’ll assume the king is at home in one of the castles he owns. We’ll also assume we’re talking about a Western European king in the High Middle Ages (1200-1350, or thereabouts).

The king or lord of a castle, and his wife, were often the only people to have a private bedroom of their own – and even here ‘private’ is a relative term, since it was normal for a servant or two to spend the night on a pallet bed in the same room, in case the king woke during the night and needed them. This bedroom was called the ‘solar’ since it was usually constructed high in the great tower of a keep, with windows to let the sunlight in. The walls would likely be stone, whitewashed or plastered, and hung with tapestries to keep out the droughts. The floor would be wooden; carpets had not been introduced yet in Europe.

As time went by, it became more common for high-ranking members of the household to have separate bedrooms; but it was not yet standard. Most people slept communally in the Great Hall, or in the case of servants on the floor of their own workplace (kitchen, stable, etc).

The king’s bed was wooden – and capable of being dismantled so the king could take it with him when going on a journey. The springs would be made of leather or rope, the mattress and pillows of linen stuffed with goose-feathers, and the bed was normally of the ‘four-poster’ design with linen curtains that could be pulled across to give the illusion of privacy from the servants sleeping a couple of metres away. It seems that people usually slept naked (those who could afford warm beds, at any rate).

On waking, the king and queen would wash their hands and face in a bowl of water brought up to the bedroom by a servant. The toilet (‘privy chamber’) was usually a small room built into the tower wall, with a simple hole in a seat overhanging the moat. Having a bath or shower was not something done as a daily routine – heating and carrying all that water up from the well in buckets was very labor-intensive, so baths were considered a special treat.

The king would then get dressed, either by himself or with the aid of servants. Typical undergarments would be a pair of linen ‘braies’ (baggy underpants, fastened around the waist by a cord tie), woolen ‘hose’ (stockings, which attached to the same cord tie as the underwear), and perhaps a linen ‘chemise’ (shirt). Then over this came a tunic, which was normally a full-length garment with long, baggy sleeves that pulled on over the head and hung down to the ground. This was a status symbol – people who had to work for a living wore shorter tunics that left their legs free. Also, while most tunics – even for nobility – were made of wool, a king might wear a tunic of silk or velvet or even cotton (which was more expensive than silk) to show off his wealth. A second tunic or ‘surcoat’ was often worn over the first one – it was generally shorter, with short, wide sleeves, and the fashion-conscious would make sure that the colors of the over-tunic and under-tunic complemented each other. Finally, a hood or mantle would be fastened around the neck – while this could be pulled up over the head to keep your ears warm, its primary purpose was actually decorative; they could be trimmed with expensive fur or jewels. Shoes and a belt completed the ensemble. There were no pockets – you tucked things into your sleeves, or hung a pouch from your belt.

Women’s clothes were not much different to men’s at this time, except that instead of a shirt and breeches, their undergarment was a linen shift. A woman’s surcoat was often sleeveless, and sometimes cut away at the sides, to emphasize her figure. Also, married women were expected to cover their hair when in public, with a cloth scarf, hat or wimple; unmarried women kept their hair uncovered, often with jeweled clips in it.

After dressing, the king would go to his private chapel, where he would hear Mass. He might then go down to the Great Hall to break his fast (that is, have breakfast) with his nobles and attendants. This was normally simple; bread and beer. (Very weak beer, not something you could easily get drunk on.) Many people did not eat breakfast at all, but instead waited until dinner, which was generally served early at about 11:00 in the morning.

The Great Hall usually covered the entire first floor of the castle (the ground floor was used for storage, and had no doors or windows for defensive reasons). There would be a fireplace either in the center of the room or against one wall. A raised dais was at one end of the hall (furthest from the entrance) where the king’s throne would be set, sometimes with a canopy over it, along with less-impressive chairs for his family, honored guests, and most important advisors. At mealtimes, benches and trestle tables would be set up in the hall, and the tables covered in clean white cloths. Afterwards, the benches could be pushed to the sides of the room to make space – and at night many of the castle staff, even those of high rank, would sleep on those benches.

There was no set routine for the king’s day, but a conscientious ruler would have plenty of official business to take care of. This can be divided into two categories – affairs of state and estate management.

The king might have policy discussions with his Council – the most powerful barons and bishops of the realm, and his chief ministers such as the Treasurer, the Chancellor and the Marshal. He would issue commands, that were noted down by royal clerks. He might administer justice – the king was considered the chief judge of the kingdom, and while this task was normally delegated the king reserved the right to hear cases in person. He might hear petitions and appeals from his subjects, and requests for him to grant them a favor or use his power on their behalf. As a rule, the latter two tasks were reserved for special occasions – the king would hold court in a castle or hall, and summon his nobles and people to appear before him so he could ‘seek their advice and counsel’ and dispense justice. These formal meetings would eventually develop into the institution of Parliament.

Estate management was vital because the king was the largest landowner in the country. Contrary to popular belief, most of the royal income in medieval times did not come from taxes (which were normally only levied in national emergencies such as a war) but from tolls, rents and income from the king’s tenants and those making use of his property. Overseeing his tenants and managing the income was a major job, and a responsible king would spend a lot of time with his stewards going over the accounts and supervising their decisions.

If the king had no official business to conduct that day, he might instead go hunting – a very popular pastime with the nobility. Most hunting was done from horseback, with the quarry being deer or perhaps wild boar. A professional huntsman with a team of dogs would flush out the quarry and corner it, then the king or his guests and companions would kill the prey with a spear or bow and arrow. Hawking and falconry were also popular pastimes – for ladies as well as knights. The prey killed would usually find its way to the royal table at dinnertime.

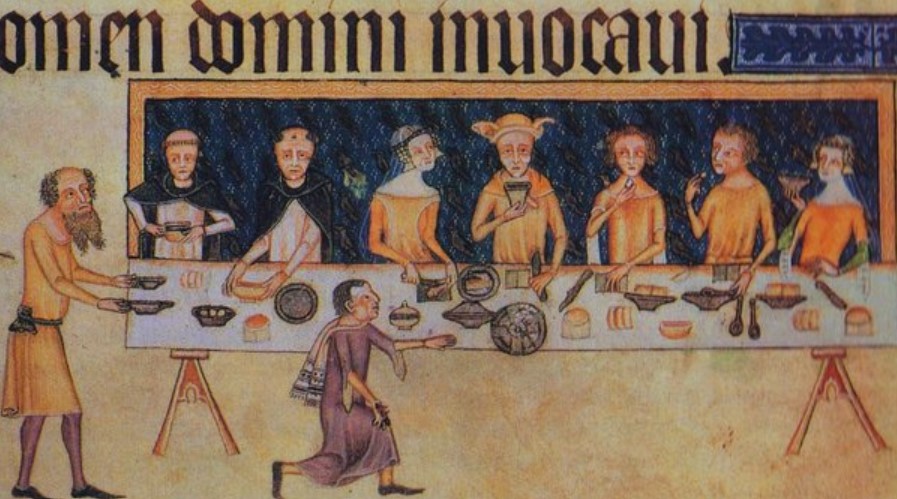

The main meal of the day was normally started early, before midday, and would go on for a couple of hours. Elaborate rituals and etiquette surrounded the meal; it was an important way for the king to demonstrate his wealth and status, and do honor to his important guests. The seating arrangement for a meal was determined according to rigid rules of precedence – the more important you were, the closer to the king you were sat. Women and men would be interspersed where possible.

It was considered polite to wash your hands before eating; a bowl of water might be set out next to the entrance to the hall to allow this, or the servants would bring ewers of water to each guest. Washing your hands between courses was also important – since the fork had not yet been invented, so people picked food up with their fingers. (Though spoons were used for soup and broth, and knives for cutting.)

Rather than plates, food was often eaten from ‘trenchers’, which were large, thick slices of slightly stale bread. These soaked up the juices from the food, and if you were especially hungry you could eat them as well. The meal would have multiple courses, and each course would often see several different dishes placed on the table, from which you could select as much or as little as you liked of each. It was considered polite to serve the person sitting next to you before yourself, if they were of a higher rank than you.

The first course of the meal was often boiled or stewed meat – pork, chicken, mutton and venison being most common – prepared with an elaborate range of strongly-flavored sauces, herbs and spices. On fast days, fish was served instead of meat – eels and lampreys, herring or pike, with more of the elaborate sauces and dressings. After the first course, fruit or nuts might be served to clear the palate.

The second course would be roast meat – often venison or game from the hunters, although this was an opportunity for extravagant hosts to impress their guests by serving exotic meat – roast peacock, for example. Salmon, turbot or lampreys might be served on fish days. Vegetables such as leeks, onions, peas and beans would accompany the meat, though often incorporated into sauces and pottages rather than being served separately. Bread was also served, and was often graded into qualities (the whiter the bread, the better) and given to guests of the appropriate status.

The third course would be fruit-based dishes – quinces, damsons, apples, pears, other fruits depending on season; often baked or candied or made into compotes. Small, expensive meat dishes might also be served such as roast sparrows or pickled sturgeon. Finally, cheese would be served at the end of the meal.

To drink, there would be either wine or beer. Wine was considered the higher status drink, so you could expect it to be served at a royal banquet – while the servants and lesser guests would get beer. By modern standard medieval wine was very rough; it had to be drunk the same year it was made (no corks and no glass bottles). As a point of interest, in the year 1363 King Edward III of England’s royal household got through 170,310 gallons of wine, most of it shipped over from Bordeaux.

Both during and after the meal there would be entertainment. Jesters actually did exist; from what we know of the medieval sense of humor people tended to enjoy slapstick, sarcasm and practical jokes, and could be rather cruel in their humor. Actors, jugglers and acrobats might also be hired to provide entertainment. Music, however, was perhaps more common; musicians would play lutes or harps or other instruments, and minstrels would sing songs and ballads. After the meal was over some of the nobles present might also give a performance of a song or poem, if they had the talent. Composing your own poem was considered a notable achievement – though we know that some noblemen paid professional troubadours to write songs for them, which they then passed off as their own!

There might also be dancing once the tables were pushed aside. Party games such as blind man’s buff were popular. Less energetic nobles might play chess or backgammon, or gamble with dice. Playing cards reached Europe towards the end of the 14th century. As for sport, bowling became so popular in the 14th century that several kings tried (unsuccessfully) to ban it since it interfered with archery practice. Jeu de paume, the ancestor of tennis, was also popular – it was played with a gloved hand rather than a racket. Football was considered a peasants’ game, and cricket hadn’t yet been developed. Various martial practices such as fencing, tilting (jousting practice) and archery might also be engaged in. People might also go for a walk or a ride outside if the weather was fine.

The second meal of the day would be served at the end of the afternoon, being smaller and simpler than dinner. The evening was usually spent relaxing; and people generally went to bed early so they could be up first thing in the morning, and make maximum use of daylight.

Authored by Stephen Tempest. MA in Modern History, University of Oxford (Graduated 1985)