Rakhi Garhi is a village in Hisar District in the state of Haryana in India, situated 150 kilometers to the northwest of Delhi. It is an Indus Valley Civilization site. A cemetery of Mature Harappan period is discovered at Rakhigarhi, with eight graves found. Often brick covered grave pits had wooden coffin in one case. Different type of grave pits were undercut to form an earthen overhang and body was placed below this; and then top of grave was filled with bricks to form a roof structure over the grave.

Parasite eggs which were once existed in the stomach of those buried were found in the burial sites along with human skeletans. Analysis of Human DNA obtained from human bones as well as analysis of parasite & animal DNA would be done to assert origins of these people.

In the late 1820s, a British explorer in India named Charles Masson stumbled across some mysterious ruins and brick mounds, the first evidence of the lost city of Harappa. Thirty years later, in 1856, railway engineers found more bricks, which were carted off before continuing the railway construction. In the 1920s, archaeologists finally began to excavate and uncover the sites of Harappa and Mohenjodaro. The long-forgotten Indus Valley civilization had, at last, been discovered.

Few Interesting Facts About Rakhigarhi Harrappa Civilization discoveries

#1. The Harappan site is the biggest one known yet—at up to 550 hectares, it’s more than twice the size of Mohenjodaro.

#2. The Rakhigarhi samples belonged to individuals who lived approximately 4,600 years ago, during the peak of the Indus Valley Civilization. The bones of four people were excavated in Rakhigarhi.

#3. The excavation and extraction of samples has been carried out under Vasant Shinde, a senior archaeologist who is the vice-chancellor at the Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute in Pune.

#4. The Rakhigarhi samples have a significant amount of ‘Iranian farmer’ ancestry. You won’t find this DNA in the north Indian population today, but only in south Indians,” says Niraj Rai (the head of the Ancient DNA Laboratory at Lucknow’s Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP), where the DNA samples from the Harappan site of Rakhigarhi in Haryana are being analyzed).

#5. Friese believes the Indus Valley Civilisation people were closer to present-day South Indians, and is quite definite that they were not the “original source of the Sanskritic language (sic) and culture of Vedic Hinduism”.

#6. The paper based on the examination of the Rakhigarhi samples would soon be published on bioRxiv (pronounced “bio-archive”), a preprint repository of papers in the life sciences.

Now we may have the answer to a few questions that have vexed some of the best minds in history and science :

Q: Were the people of the Harappan civilisation the original source of the Sanskritic language and culture of Vedic Hinduism?

A: No.

Q: Do their genes survive as a significant component in India’s current population?

A: Most definitely.

Q: Were they closer to popular perceptions of ‘Aryans’ or of ‘Dravidians’?

A: Dravidians.

Q: Were they more akin to the South Indians or North Indians of today?

A: South Indians.

All loaded questions, of course. A paper suggesting these conclusions is likely to be online in September and later published in the journal Science.

Before going to final conclusions you must think on these points as well.

# Indus Valley area was multi-ethnic and multi-linguistic. Crucially, the skeletons in the cemeteries are believed to account for only a small fraction of the population of the cities. Obviously, a large number of Harappans were disposing of their dead by cremation or exposure (as the Zoroastrians do). Thus, there were populations living in the Indus cities whose remains we may never find.

# The DNA obtained from the available skeletons will not be representative of the entire Bronze Age Indus population.

# The skeletons at Harappa showed similar levels of nourishment, implying they belonged to people of one economic group. Startlingly, analysis also suggests the skeletons interred hundreds of years apart in Harappa and Farmana, about 50 kilometres from Rakhigarhi, may all have belonged exclusively to first generation migrants to the region. We do not know why this is so, but there was probably some form of regulation of movements of populations from outside the region. To that extent, one wonders if it would be correct to say the skeletons belonged to Indus Valley people at all.

Read Full story:

Niraj Rai, the head of the Ancient DNA Laboratory at Lucknow’s Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP), where the DNA samples from the Harappan site of Rakhigarhi in Haryana are being analysed, has revealed that a forthcoming paper on the work will show that there is no steppe contribution to the DNA of the Harappan people. This result comes close to settling one of the most important outstanding issues regarding the Indian past—the question concerning the possible migration of Indo-European language speakers from the Pontic steppe in Central Asia into north-west India.

“It will show that there is no steppe contribution to the Indus Valley DNA,” Rai said. “The Indus Valley people were indigenous, but in the sense that their DNA had contributions from near eastern Iranian farmers mixed with the Indian hunter-gatherer DNA, that is still reflected in the DNA of the people of the Andaman islands.” He added that the paper based on the examination of the Rakhigarhi samples would soon be published on bioRxiv (pronounced “bio-archive”), a preprint repository of papers in the life sciences.

The Rakhigarhi samples belonged to individuals who lived approximately 4,600 years ago, during the peak of the Indus Valley Civilisation. The absence of steppe DNA markers in the samples indicates that, at that point in time, there had been no intermingling between the steppe pastoralists and the population of the Indus Valley Civilisation.

The bones of four people were excavated in Rakhigarhi. According to Rai, three samples from Rakhigarhi were morphologically well preserved, but the DNA that was extracted from them was highly degraded. “But we were able to obtain a good sample,” he said. The excavation and extraction of samples has been carried out under Vasant Shinde, a senior archaeologist who is the vice-chancellor at the Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute in Pune. The Rakhigarhi study, Rai said, provides direct evidence for the claims of a paper published in preprint on bioRxiv in March 2018, which outlines a comprehensive model for the settlement of different populations within the subcontinent.

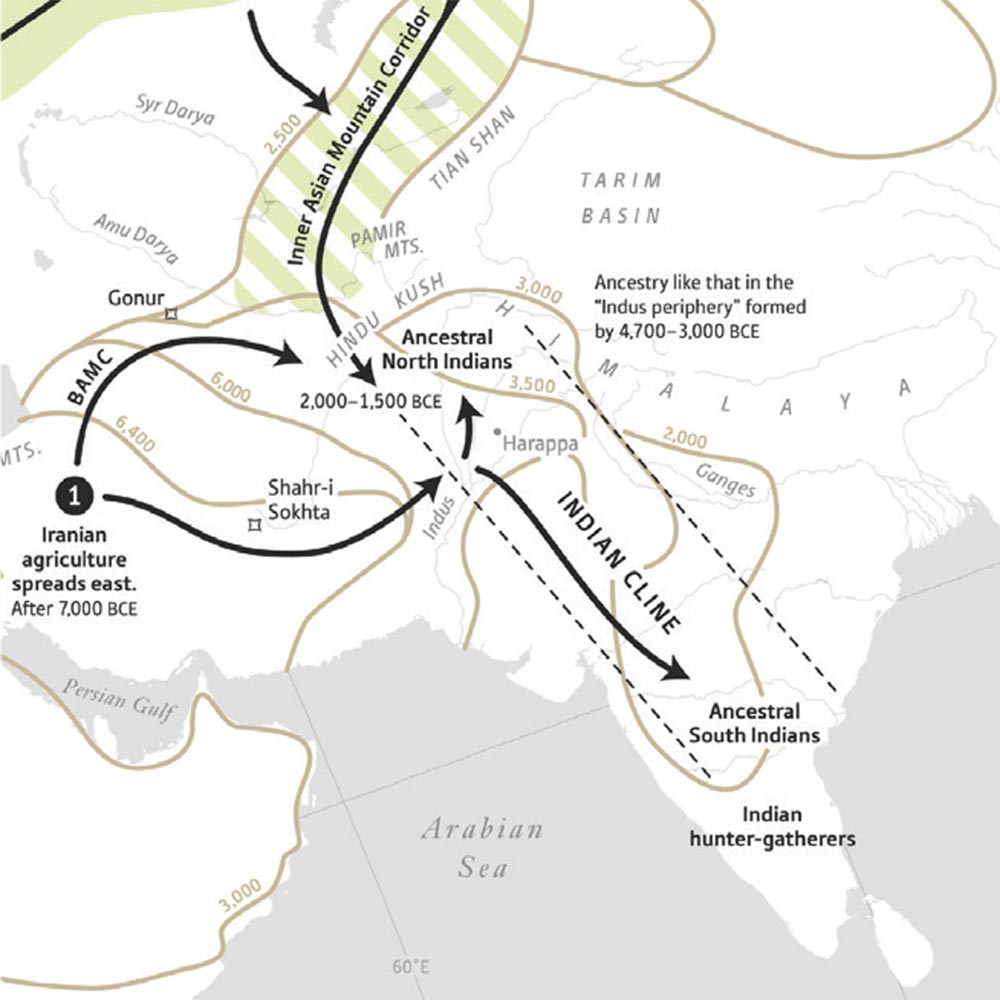

Shinde and Rai are among 91 co-authors of this March 2018 paper, titled “The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia.” The study was carried out at the laboratory for ancient DNA at the Harvard Medical School, which is run by David Reich, a geneticist and a professor in the college’s department of genetics. The model proposed in the paper elaborates on a 2009 paper from the lab that suggests the current population of India is largely an admixture in varying proportion of two older populations—the Ancestral North Indians (ANI) and the Ancestral South Indians (ASI).

The March 2018 paper posits two migrations into South Asia—the first, by Iranian farmers less than 9,000 years ago, and the second, by the steppe pastoralists less than 5,000 years ago. The first migration mingled with the pre-existing hunter-gatherer population of South Asia and gave rise to what the authors’ term the Indus Periphery People—the latest study clarifies that this represents the population of the Indus Valley Civilisation, and not another distinct population. The second migration of steppe people, which coincided with the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization, around 4,000 years ago, mixed with the Indus Periphery People to give rise to the ANI population. Simultaneously, the Indus Periphery People also migrated southward and further mixed with the indigenous hunter-gatherers who lived in the area to give rise to the ASI population. Most Indians today are the subsequent admixture of the ANI and the ASI populations.

The paper, however, does not include a study of any ancient DNA from the Indus Valley people, a lacuna that will be filled only when the paper Rai referred to becomes available. In its absence, the study that was published in the March 2018 paper used a stand-in population, whose DNA was based on that of three outlier samples of ancient DNA from between 4000 and 5000 years ago, which were found in the eastern Iranian region, and whose DNA profile resembles that of 41 other samples from the Swat site of the Indus Valley from a millennium later, after its decline.

Rai said that he and his team at the BSIP agreed to be a part of the March 2018 paper “after two years of intense discussion and analysis of our own data sets.” He continued, “There is no question of the model being flawed. It is a most solid piece of work—no new study will overturn it. Our own work which will be out very soon provides solid evidence for the model.”

Rai had earlier told Open magazine that the male “Y chromosome R1a genetic marker is missing in the Rakhigarhi sample.” The R1a is seen as a marker of Indo-European speakers, but its absence in a single sample is not significant—it is the wider analysis of the entire genome that is important in the context of this sample.

The work by Rai and his team will provide direct evidence for the model proposed by the March 2018 paper from the Reich Lab, which has bearing on a number of questions of great interest pertaining to the Indian past. The preprint states, “Our results also shed light on the question of the origins of the subset of Indo-European languages spoken in India and Europe. It is striking that the great majority of Indo-European speakers today living in both Europe and South Asia harbor large fractions of ancestry related to … Steppe pastoralists … suggesting that ‘Late Proto-Indo-European’—the language ancestral to all modern Indo- European languages—was the language” of the steppe pastoralist population.

In other words, the preprint observes that the migration from the steppes to South Asia was the source of the Indo-European languages in the subcontinent. Commenting on this, Rai said, “any model of migration of Indo-Europeans from South Asia simply cannot fit the data that is now available.”

Mapping Ancestry

Migrations affecting ancient Central and South Asian populations (courtesy the March 2018 genome study)

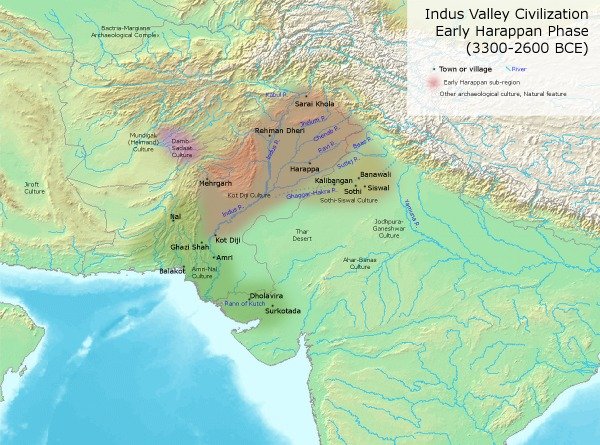

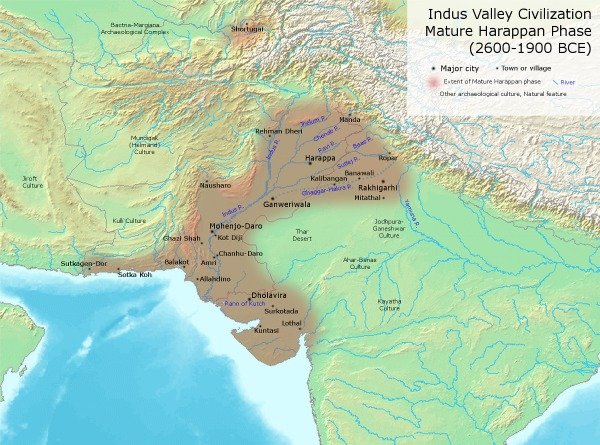

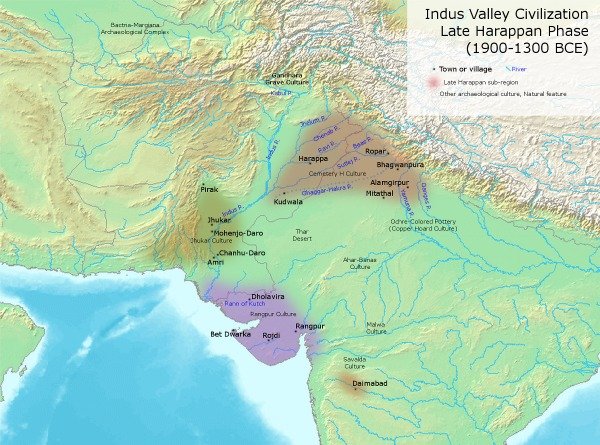

Phases of Indus Valley Civilization